Contains spoilers for Pentiment.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock since the summer, you might have heard that Gladiator 2 came out. I still haven’t seen it, but even before it was released in the UK, I was asked by multiple people how I ‘felt’ about its historical accuracy ‘as a classicist’: as someone who spent four years of my life studying cultures around the ancient Mediterranean. Gladiator 2 also probably prompted these questions because of Ridley Scott’s attitude to historical accuracy in his Napoleon press tour. If you haven’t already seen it, I feel privileged to be the first to show you, “When I have issues with historians, I ask: ‘Excuse me, mate, were you there? No? Well, shut the f*** up then.’” (… I unironically love this quote.)

This question of ‘accuracy’ – Scott’s antagonism towards it, and the assumption that my experience studying the ancient world would make me dislike Gladiator 2 (which might yet be true) – has prompted a movement to dissect historical fiction across media forms in recent years. So-called ‘breakdowns’ of TV and films have been particularly popular: I know of at least one historian who has already dissected Gladiator 2‘s many historical blunders, and this video on the 2004 film Troy has over a million views.

But the best of these do more than just say whether something is ‘right’ or ‘wrong’: they underscore how historians and creatives might have radically different interpretations of their primary sources. Bret Devereaux’s blog on Gladiator 2 doesn’t just tell us how the film is innaccurate, but how Scott’s interpretations are particularly ‘ill-fitting’ for the time period in which it is set. And in the Troy breakdown, Roel Konijnendijk points out how modern assumptions have influenced the film’s deviations from the Iliad. Konijnendijk argues that the film presents Agamemnon as an imperial expansionist, in order to explain why the Greeks went to Troy. This contrasts with the Iliad’s own focus on Helen’s abduction/choice to leave, and how it invoked unbreakable ties of obligation – created by oaths and societal hierarchies – among various Greek leaders. But these breakdowns rest, in some way, on the premise that one can measure how faithfully a historical truth is recreated, or how badly it is obscured, in these pieces of media.

These conversations made me think more about what makes historical games unique, in contrast to films, TV shows, or books. I’m going to look at non-linear narrative here, especially since I grew up mostly playing games with branching storylines like Skyrim, Witcher, or Dragon Age. But I’ve noticed that when historical games have non-linear narrative elements, they tend to present a binary between ‘real’ and counterfactual history (i.e. what-if scenarios about people or events). The whole premise of Crusader Kings III, for example, encourages players to think of their gameplay as exploring alternate histories after the death of a real monarch or historical figure: even if these scenarios end up being as whacky as consuming the Pope.

This idea also came up in a 2023 GDC talk, where Soren Johnson explored how player behaviour often mismatches with developer intent when making games. He touched upon historical wargames, arguing that “one of the basic challenges” when designing them is “how to encourage historical play when no one knows what the likely or even plausible alternate results could be. For example, could the South have ever won the Civil War?” In other words, player choices can either represent harmony with, or deviation from, a definable historical reality: a true version of events.

Dr James Coltrain highlighted another way to bring historiographical creativity into game development. In his 2019 GDC talk ‘A Historian’s Guide to Researching Your Historical Game’, he pointed out that, “It’s important for us to think about how we [i.e. game designers] interpret evidence, because when we recreate a historical world in our game, we’re actually creating our own historic interpretation.” He argued that history is not a linear narrative, but instead a conversation: the same set of evidence can be interpreted in many different ways by different historians. To illustrate this, Coltrain gave the example of Andrew Jackson being far more highly praised by nineteenth-century historians than those today, as well as Christopher Columbus. The design choice he emphasises, then, is that developers can select which historical interpretations to highlight or interrogate, in ways which align with the story they want to tell.

So, these are two trends I’ve noticed – non-linear narrative as a way of exploring alternate histories, and then the idea that game designers can – and should – choose to use interpretations of history which align with the story they want to tell. Both are great: nothing wrong with either approach, and I love playing games which utilise both!

But something else, which I haven’t seen discussed as much, are the genuinely grey areas in history. Specifically, I’m thinking about moments where there are competing interpretations of the same pieces of evidence, or where different pieces of evidence present conflicting versions of events.

Let me give an example. In 415 BCE, the city of Athens prepared a huge fleet to sail to Sicily, in the middle of the Peloponnesian War. However, before the fleet left, the city of Athens woke up one morning to discover that many statues called herms (ἑρμαῖ, hermai) were damaged in a similar way: this would become known as the Mutilation of the Herms.1

I should say that herms are bizarre statues. In this period in Athens, they consisted of a head depicting the Greek god Hermes on a pillar, with a phallus stuck onto the front of it. (Pictures explain better than words in this instance, so I’ve included a photo of an example made around a hundred years before the Mutilation itself.)

Exactly how and – to some extent – where these statues were damaged is unclear. The Greek author Thucydides states that unknown culprits mutilated (περιεκόπησαν, periekopēsan) the statues’ faces (τὰ πρόσωπα, ta prosōpa), whereas the playwright Aristophanes implies in Lysistrata that the phallus on the statue might have been broken off or damaged.2 The motivation behind such attacks is also murky. Some scholars have wondered whether they were damaged just for fun, but Thucydides tells us that some in the city feared it was part of a conspiracy (ξυνωμοσίᾳ, xunōmosia) to overthrow democracy (δήμου καταλύσεως, dēmou kataluseōs), and an ill-omen for the so-called Sicilian Expedition.3 But how exactly attacking statues conveys an antidemocratic threat has been subject to debate.

I don’t have space to go into too much detail, but scholars such as Robin Osborne, and Josephine Quinn have proposed different ways of thinking about how the herms might be connected to democracy. Osborne argues that herms’ gaze represents a kind of collective identity – ‘the face of every Athenian’. Therefore, damaging them could represent a threat to the Athenian democracy by extension.

Quinn instead contrasts the herms with another, older statue type (κοῦρος, kouros, pl. kouroi), more associated with aristocratic elites, arguing that herms were originally made to undermine kouroi as symbols: they might represent a democratic mocking of the old elite system. One of the best pillars in her argument is that the herms’ relative large phalluses might deliberately contrast with the smallness of those on kourai. Therefore, an attack on herms – and especially one which might have involved knocking off their phalluses – translates to an attack on democracy. In addition to this uncertainty about the motivations behind the Mutilation, it’s also unclear whether a prominent figure named Alcibiades orchestrated the event: Thucydides records that people blamed him for it, but Alcibiades himself denied any involvement.4

The basic point I want to make here is that we don’t know for certain what possessed a bunch of people in Athens to damage these statues: we might never know. But exploring the various reasons why, and arguing over what makes one reason more plausible than others, can do much to enrich our understanding of fifth-century Athenian society. In order to do this, historians have to think through a multitude of various possibilities and interpretations.

What would a game look like, then, which recreated this scenario with all its different possibilities? Could it tell the story of the Mutilation through the eyes of one of the suspects? Were they antidemocratic conspirators? Were they a bunch of drunk young men who thought it would be funny to knock the dicks off some statues? Was Alcibiades behind it after all, or was he as innocent as he claimed? And what if a player could choose between all of these situations: either egging on a drunken group because it would be funny, or helping an antidemocratic faction plan it? In creating these branching storylines, how might they challenge audiences’ assumptions about ancient Greece: underscoring the different political factions at play in Athens, the fragility of the Athenian democracy, how democracy as an idea was radically different from our own today, showcasing aristocratic life in the city as opposed to military history?

Games have a unique opportunity to play with such acts of historical interpretation. In films, books, and TV, it’s much harder to convey this sense of competing realities without turning the genre into something sci-fi adjacent, like Everything, Everywhere, All at Once: the scene in The Green Knight where Gawain is taken captive comes to mind, too. But it’s common to have different endings and choices throughout a game, which could be used to explore these knots of ambiguity in historical sources. Focusing on the plausibility of events, rather than their binary, true-or-false ‘accuracy’, and allowing players to explore different interpretations of certain historical moments, could be just as interesting a way to write historical narratives in games.

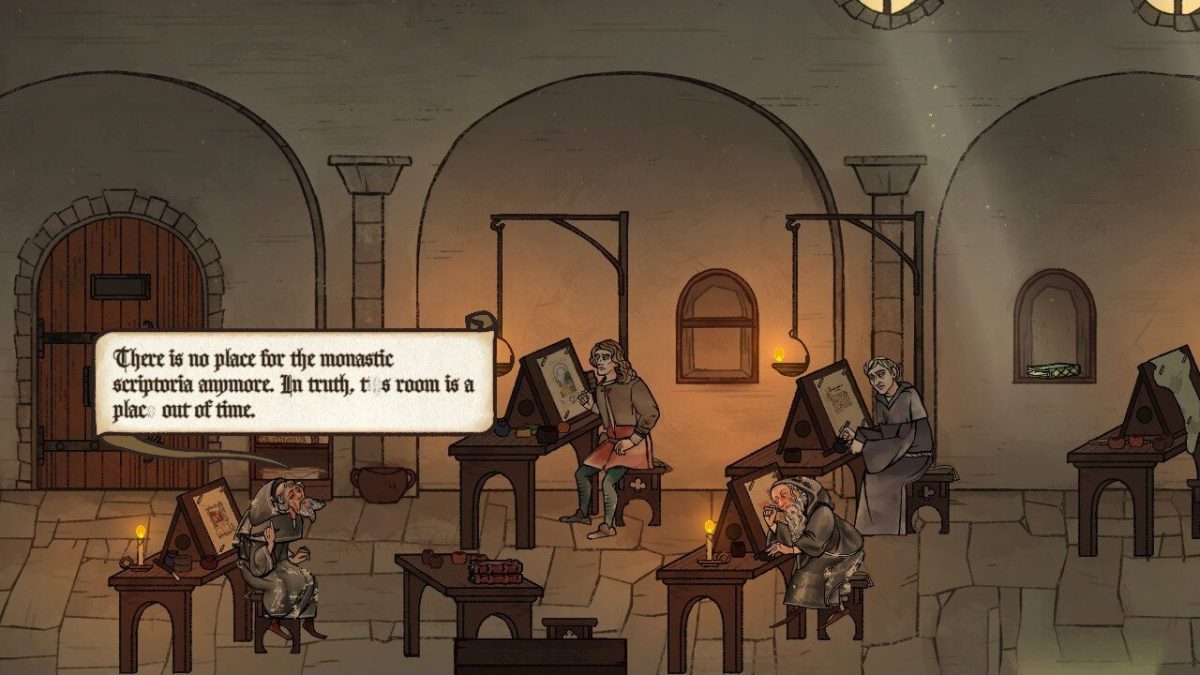

This isn’t to say the presentation of multiple, conflicting versions of historical events has never been done before in games. Pentiment made me think about this, but perhaps not in the way you might initially think. It is, of course, a historical game, lauded for the detail and nuance it brought to its sixteenth-century setting. But it was its approach to the murder-mystery aspects of its story which I feel really emulated the act of historical interpretation.

If I can be excused for using various forum posts and articles as a crude straw poll of players’ views, some had wildly different interpretations of same pieces of evidence when investigating the murders. Some people thought that some pieces of evidence were more important than others (Matilda’s shovel, for example); some argued that characters were unreliable narrators; others argued that the definition of ‘murderer’ was malleable, using wider social and political circumstances to make their case. For example, Brother Guy technically caused the abbot to raise the Abbey’s taxes, so isn’t he really Otto’s true murderer? In other words, putting the player in an interpretive role encouraged them to think in a similar manner to a historian.

Pentiment was by no means the first to use murder-mystery tropes to encourage players to think in this way. The Case of the Golden Idol and Return of the Obra Dinn also encouraged their players to become historical detectives, and to use their skills of deduction to find out what happened in the game’s story. But both require the player to come to a single, correct version of events in order to complete the game. By contrast, Pentiment refuses to commit to a ‘real’ culprit. The player never finds out who killed the victims: so, arguably, their choice becomes the one plausible historical interpretation amongst many.

There are other ways in which Pentiment conveyed a plurality of historical realities. Aspects of Andreas’ background – for example, where he might have spent his Wanderjahre – are left to player choice. This allows players to perform a variety of different historical realities, more or less equally plausible for a man of Andreas’ social stature from Nuremberg at this time. In doing so, Pentiment not only informs its audience of its historical setting, but allows players to create their own interpretation within that setting. Pentiment’s ability to hold the tension between multiple historical realities, then, encapsulates these specific nuances of historical interpretation more than I’ve (yet) seen in another game.

So, to tie up this meandering set of thoughts: what I’ve been trying to say is that there have been many conversations about historical accuracy across all media forms. However, these conversations have tended to give the impression that there’s one true version of events which creatives can either adhere to, or drift away from. Instead, I’ve pointed out that there’s often a great deal of ambiguity in attempting to recreate ‘what actually happened’. And instead of that causing a problem (where developers might feel forced to ‘choose’ a single interpretation), the unique format of games offer a chance to do historical fiction differently to any other medium.

I’ve proposed that one way of achieving this is to allow players to choose different historical interpretations of the same event. It might seem like I’m setting up a discrete contrast here, but using differing historical interpretations as non-linear narratives still requires a fundamental commitment to historical accuracy: it wouldn’t really be in the spirit of it to offer one choice that leads to, say, aliens knocking dicks off the herms (although… that could be a creative sci-fi plotline). All of this is to say that games can invite their audiences to be part of the intellectual process of interpretation: they can not just reflect a historical setting, but emulate what history fundamentally is as a discipline.